The Architecture Behind GigaChad GRC: Patterns for Building Extensible Compliance Platforms

A follow-up to Building Your Own GRC Stack

When I published the first post about building GigaChad GRC, I expected a few comments and maybe some skeptical DMs. What I got instead was a wave of practitioners asking the same question: how did you actually architect this thing?

The original post covered the why—the frustration with vendor lock-in, the six-figure platforms that couldn’t match Google Apps Script, the decision to stop asking permission. But it only scratched the surface of the how. This post goes deeper.

Over the past months, I’ve received pull requests, feature suggestions, and deployment stories from practitioners who’ve actually run this in production. That feedback has validated some architectural decisions and exposed others as premature optimization. Here’s what I’ve learned about building a GRC platform that doesn’t paint you into a corner.

Why Architecture Matters More in GRC

Most software architecture advice assumes you’re building a product with a defined scope. GRC is different. Every organization has a unique control environment, bespoke risk categories, industry-specific frameworks, and auditors with their own preferences. A rigid architecture becomes a straitjacket.

The goal wasn’t to build a platform that handles every use case out of the box. It was to build a platform where adding your use case doesn’t require a fork.

That distinction shaped every major decision.

The Case for Microservices (And When It Actually Makes Sense)

Conventional wisdom says start monolithic, split later. For most applications, that’s right. But GRC has a property that makes early decomposition worthwhile: naturally bounded domains.

Controls are not risks. Vendors are not audits. Policies are not questionnaires. These domains have clear boundaries, different stakeholders, and independent lifecycles. When your auditor asks for changes to the audit portal, you shouldn’t be touching the risk register codebase.

The Domain Boundaries

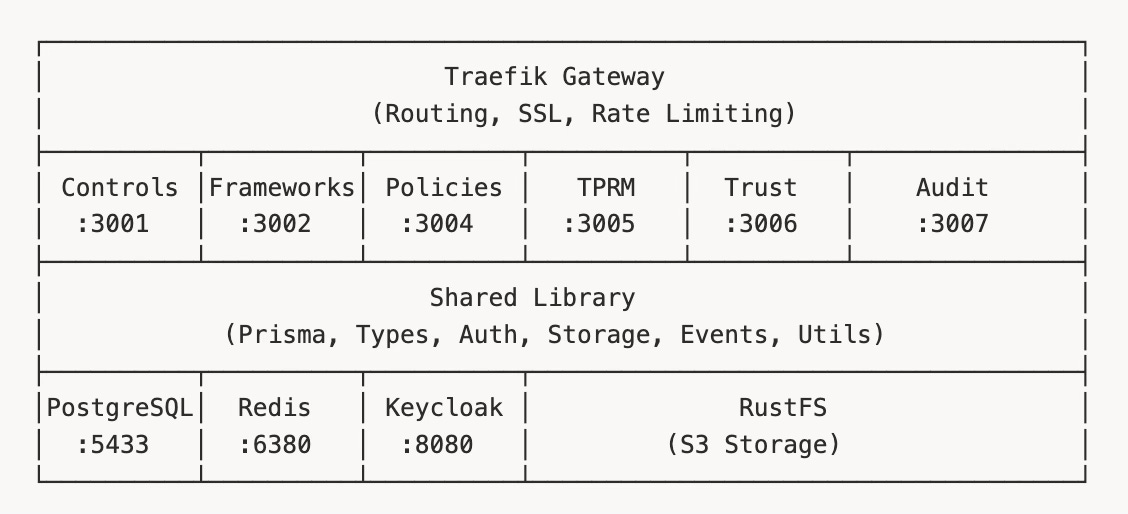

GigaChad GRC splits into six core services:

Controls - Control library, evidence management, testing

Frameworks - Framework requirements, risk management, assessments

Policies - Policy lifecycle, versions, approvals

TPRM - Vendors, assessments, contracts

Trust - Questionnaires, knowledge base, trust center

Audit - Audit Management, requests, findings, auditor portal

Each service owns its domain completely. The Controls service doesn't know how vendor assessments work. The Audit service doesn't care about policy approval workflows. They communicate through well-defined APIs and a shared event bus when necessary.

What Actually Worked

Independent deployment. When I rebuilt the Audit service to add the external auditor portal—complete with access codes, temporary permissions, and document request workflows—I deployed it without touching any other service. Zero coordination. Zero risk to the control testing that was running in production.

Isolated failure domains. A bug in the Trust service’s questionnaire parsing doesn’t crash risk assessments. Services can be unhealthy independently, and the platform degrades gracefully.

Focused codebases. Each service is small enough to hold in your head. New contributors can understand the Policies service in an afternoon without learning how vendor assessments work.

What Didn’t Work (And What I Changed)

Distributed debugging is painful. When a request touches three services, tracing the failure path requires correlating logs across containers. I added correlation IDs to every request, propagated through the event bus and HTTP headers. Should have done it from day one.

Service discovery added friction. Early on, I was doing manual service location through environment variables. It worked, but adding a new service meant updating every other service’s configuration. Traefik as the API gateway solved this—services register themselves, and routing happens automatically.

Initial setup overhead. Six services means six things to start, monitor, and maintain. For development, I created a single docker compose up that brings everything up correctly ordered. For practitioners who just want to evaluate the platform, there’s now a ./start.sh that handles the complexity.

The Real Lesson

The microservices approach worked because the domain boundaries were clear before I wrote any code. If you’re building GRC tooling and your domains blur together—if you can’t articulate where controls end and risks begin—start with a modular monolith. Microservices are a deployment strategy, not an architecture. Get the boundaries right first.

API-First: If You Can’t Script It, You Haven’t Built It

Here’s a test for any GRC platform: can you create a control, link it to a framework requirement, upload evidence, and mark it tested—entirely through API calls, with no UI?

If the answer is no, you’ve built a dashboard, not a platform.

Every feature in GigaChad GRC is an API endpoint first. The React frontend is just one client among many. This isn’t architectural purity for its own sake—it’s the foundation for everything that makes the platform actually useful.

Why API-First Matters for GRC

Automation scripts replace manual evidence collection. That AWS config you need to pull quarterly? Script it. The GitHub branch protection rules auditors want screenshots of? API call to GitHub, API call to upload evidence, done. The grc-evidence MCP server does exactly this for AWS, Azure, GitHub, Okta, Google Workspace, and Jamf.

AI integration becomes possible. The grc-ai-assistant MCP server uses the platform APIs to provide risk analysis, control recommendations, and policy drafting. It couldn’t exist if the platform required clicking through UIs.

Custom integrations don’t require forks. Want to sync controls with Jira? Pull risk data into your data warehouse? Trigger Slack notifications on audit findings? Build it against the API. Your integration survives platform upgrades.

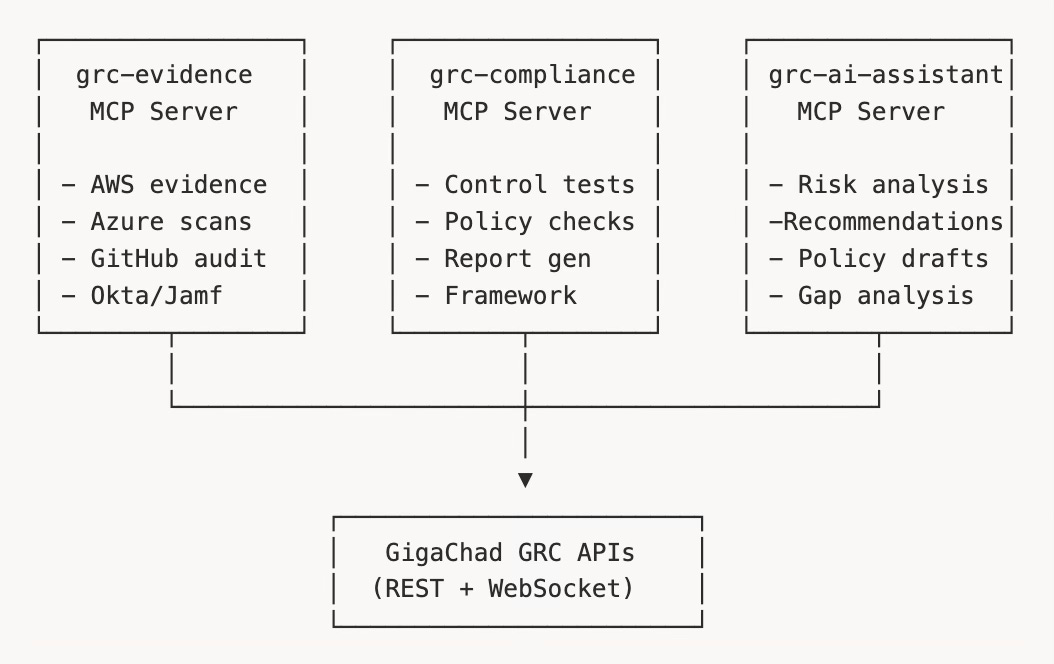

The MCP Server Architecture

Model Context Protocol servers are the ultimate test of API-first design. They’re external processes that interact with the platform entirely through APIs, enabling AI-powered automation.

Each MCP server is a standalone package that can be used with any AI tool supporting the protocol—Claude, Cursor, custom agents. They consume the platform APIs to:

grc-evidence: Collect evidence from cloud providers and security tools automatically

grc-compliance: Run control tests, validate policies, generate reports

grc-ai-assistant: Provide AI-powered analysis, recommendations, and drafting

The MCP servers proved the architecture. If an external AI tool can operate the platform effectively through APIs alone, the API design is working.

Swagger as a First-Class Citizen

Every service exposes Swagger documentation at /api/docs. This isn’t generated as an afterthought—it’s maintained as part of the development workflow. When someone opens a PR that adds an endpoint, the Swagger docs are part of the review.

The result: practitioners can explore the API interactively before writing any code. No guessing at parameter names or response shapes.

Shared Infrastructure: The Glue That Doesn’t Become Glue Code

Six microservices sounds clean until you realize they all need authentication, database access, file storage, event publishing, and consistent error handling. Duplicate that code across services and you’ve created a maintenance nightmare.

The services/shared/ library is the solution—a TypeScript package consumed by every service, providing:

What’s Shared

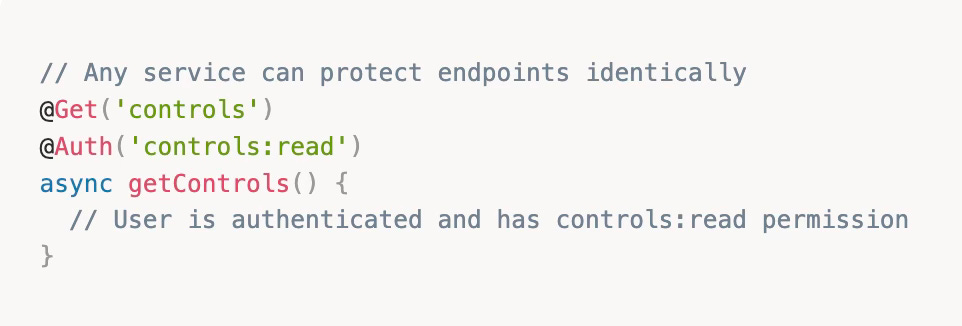

Authentication middleware. Keycloak JWT validation, role extraction, permission checking. Every service uses the same @Auth() decorators and guards. Add a new role in Keycloak, and every service respects it immediately.

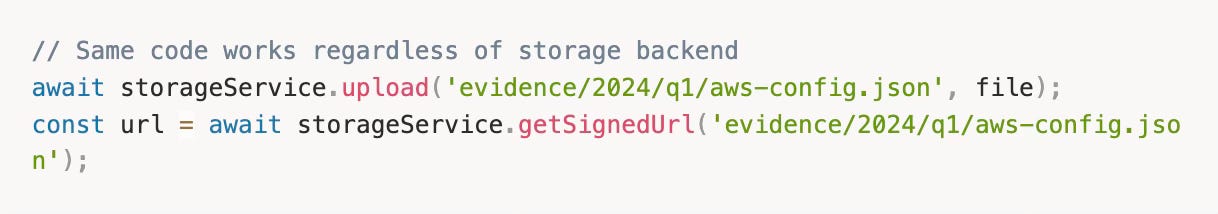

Storage abstraction. Evidence files might live on local disk, S3-compatible storage (RustFS), or Azure Blob. The shared storage service provides a consistent interface:

Swap backends by changing environment variables. No code changes.

Event bus. When controls need to notify the audit service about test completions, they publish events to Redis. The audit service subscribes without knowing which service published.

This keeps services decoupled while enabling necessary coordination.

Type definitions. Shared TypeScript types ensure the Controls service and Audit service agree on what a “control” looks like. No runtime surprises from schema drift.

Prisma client. One database schema, one Prisma client, consumed by all services. Migrations run once. The schema is the source of truth.

Why a Shared Library Instead of Shared Services

I considered the alternative: dedicated auth service, dedicated storage service, dedicated event service. Each microservice would call these shared services via HTTP.

The problem: latency multiplication. A single request that needs auth, then storage, then events becomes four network hops. For a GRC platform where users are clicking through controls and uploading evidence, that latency compounds into frustration.

The shared library approach means auth happens in-process. Storage calls go directly to the backend. The services share code, not network round-trips.

The Single Database Decision

Yes, all services share one PostgreSQL database. This is controversial in microservices circles, but for GRC it’s pragmatic.

The reality: GRC data is deeply interconnected. Controls link to frameworks. Risks link to controls. Evidence links to everything. Enforcing strict database-per-service boundaries would mean constant API calls between services for basic operations, or maintaining complex data synchronization.

The tradeoff: Services must respect each other’s tables. The Controls service doesn’t write directly to audit tables. This is enforced through code review and convention, not database permissions. It works because the team is small and the domain boundaries are clear.

When to split: If services need to scale independently or you have teams that can’t coordinate, separate databases make sense. For most GRC implementations, the operational simplicity of a single database wins.

Extensibility Without Fork Anxiety

Here’s the scenario that kills most open-source platforms: a practitioner needs something slightly different. They fork. They modify. Six months later, they’re maintaining a divergent codebase that can’t take upstream updates. They might as well have built from scratch.

GigaChad GRC is designed with explicit extension points that don’t require touching core code.

Adding Integrations

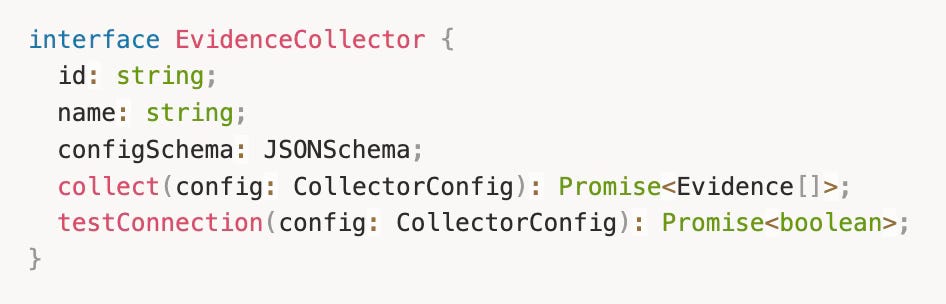

The integration architecture follows a consistent pattern. Every integration implements the same interface:

Adding a new integration means:

Create a new collector implementing the interface

Register it in the collector registry

Done

Your custom integration for that weird compliance tool your industry requires? It works the same way as the AWS integration. Submit a PR if it might help others. Keep it private if it’s organization-specific.

Adding Framework Requirements

Frameworks are data, not code. Adding NIST 800-53 or a custom internal framework means:

Create a JSON file with requirements

Import via the API or seed script

Map to existing controls

The platform doesn’t care if it’s SOC 2 or your proprietary framework. The data model is generic.

Adding Services

Need a module that doesn’t exist? The architecture supports adding new services without modifying existing ones:

Create a new NestJS service following the established patterns

Import the shared library for auth, storage, events

Add a Dockerfile following the existing template

Register with Traefik via labels

The frontend can call it like any other service

The Audit service was added this way after initial launch. Zero changes to Controls, Frameworks, or any other service.

MCP Servers as the Ultimate Extension

For automation that doesn’t fit neatly into the platform, MCP servers provide unlimited flexibility:

Run on your infrastructure

Use any language (TypeScript reference implementations provided)

Consume platform APIs for data

Integrate with AI tools or run standalone

No deployment coordination with the platform

This is the escape hatch that prevents forks. If the platform doesn’t do something, script it via API. If you need AI assistance, build an MCP server. The core platform stays maintainable.

Deployment Flexibility: Your Infrastructure, Your Rules

The same codebase deploys three different ways:

Option 1: Terraform for AWS

Full enterprise deployment with:

VPC with proper isolation (public/private subnets)

ECS Fargate services with auto-scaling

RDS PostgreSQL with encryption and automated backups

ElastiCache Redis cluster

ALB with SSL termination

S3 for evidence storage

Secrets Manager for credentials

Run terraform apply and have production infrastructure in 30 minutes. The Terraform modules are in terraform/modules/ and document every decision.

Option 2: Docker Compose for Single Server

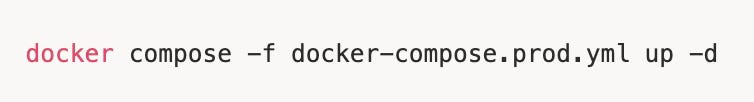

For teams that need production-ready deployment without AWS complexity:

This gives you:

All services running on one machine

PostgreSQL, Redis, Keycloak, RustFS included

Traefik handling routing and SSL

Automatic health checks and restarts

Backup scripts included

Many production deployments run this way. A well-provisioned single server handles more load than most GRC programs generate.

Option 3: Managed Infrastructure (Supabase + Vercel)

For teams who want managed services:

Supabase for PostgreSQL

Vercel for frontend and serverless functions

External Redis (Upstash, etc.)

Cloud storage for evidence

This path trades operational control for operational simplicity.

The Philosophy: Works on My Laptop, Works in Production

The same docker compose up that runs locally runs in production. The same environment variables. The same container images. No “works on my machine” surprises.

The Terraform modules and Docker Compose files aren’t separate configurations—they’re alternative deployment targets for identical containers.

What I’d Do Differently: The Honest Retrospective

Community feedback and production usage revealed decisions I’d reconsider.

Should Have Done Earlier

Correlation IDs from day one. Distributed tracing is painful to retrofit. Every HTTP request and event should carry a correlation ID that flows through the entire request path. I added this after debugging a cross-service issue took two hours.

Feature flags. Some organizations need controls but not risks. Some need TPRM but not audits. Adding feature flags to disable modules without removing code would have made the platform more adaptable. This is now partially implemented but should have been foundational.

Better migration tooling. Database migrations work, but rollback is manual. Organizations upgrading production need confidence that a bad migration won’t require database restoration.

Decisions That Paid Off

API-first from the start. The MCP servers validated this immediately. AI tooling integration was trivial because the APIs were already comprehensive.

Shared library over shared services. In-process shared code keeps latency manageable and deployment simple.

Traefik as the gateway. Automatic service discovery and configuration via Docker labels eliminated a category of configuration management.

RustFS over MinIO. Switching to RustFS for S3-compatible storage reduced resource usage and stayed Apache 2.0 licensed. The storage abstraction made the swap transparent.

Community Feedback That Changed My Thinking

Several practitioners asked for simpler initial deployment—the full microservices setup was intimidating for evaluation. The ./start.sh script and simplified getting-started guide came directly from this feedback.

Others wanted more granular permissions. The initial RBAC model was too coarse. The current implementation supports permissions like controls:read, controls:write, controls:test—fine-grained enough for real organizational structures.

The most repeated request: better documentation for extending the platform. The architecture supports extension, but knowing where to start wasn’t obvious. This post is part of addressing that.

Closing: Architecture as Philosophy

Vendor platforms optimize architecture for their business model. API access becomes a premium tier because restricting it drives upgrades. Customization requires professional services because flexibility cannibilizes support revenue. The architecture serves the vendor.

Practitioner-built platforms optimize for the actual work. APIs are open because automation is the point. Customization is encouraged because every organization is different. The architecture serves the user.

The decisions documented here—microservices along domain boundaries, API-first design, shared infrastructure without shared services, explicit extension points, flexible deployment—aren’t technically novel. They’re the obvious choices when you’re building for yourself instead of building for profit extraction.

That’s the real lesson. Technical decisions compound. Every choice either opens doors or closes them. Vendor platforms close doors strategically—they call it their moat. Practitioner platforms keep doors open because we’re the ones who need to walk through them.

Get Involved

The codebase is on GitHub. The architecture described here is what you’ll find in services/. The MCP servers are in mcp-servers/. The Terraform modules are in terraform/modules/.

If you’ve built extensions, integrations, or just found better ways to do something—pull requests are welcome. If you’ve deployed this in production and have war stories—the GRC Engineering Discord wants to hear them.

The vendor monopoly on GRC tooling was always optional. The architecture to replace it is here.

The author still maintains this platform, still drinks too much coffee, and still believes practitioners build better tools than vendors.

Related Links: