The Hidden Costs of Building Your Own GRC Platform

A follow-up to Building Your Own GRC Stack

Pierre-Paul Ferland left a comment on my architecture post that deserves a full response:

“Great stuff! I like how you explain the tradeoffs of shared libraries vs shared services and shared database vs database per service. Also, as a ‘biased towards buy’ person, it shows the tradeoffs that a team has to think about when weighing in on a commercial platform vs DIY: do you really have the headcounts to worry about traceability in each header, transaction IDs, network hops, etc.”

He’s right. My previous posts focused on the upside—escaping vendor lock-in, building exactly what you need, the satisfaction of owning your stack. This post addresses the other side of the ledger.

I built GigaChad GRC. Here’s what it actually cost.

The Costs I Expected

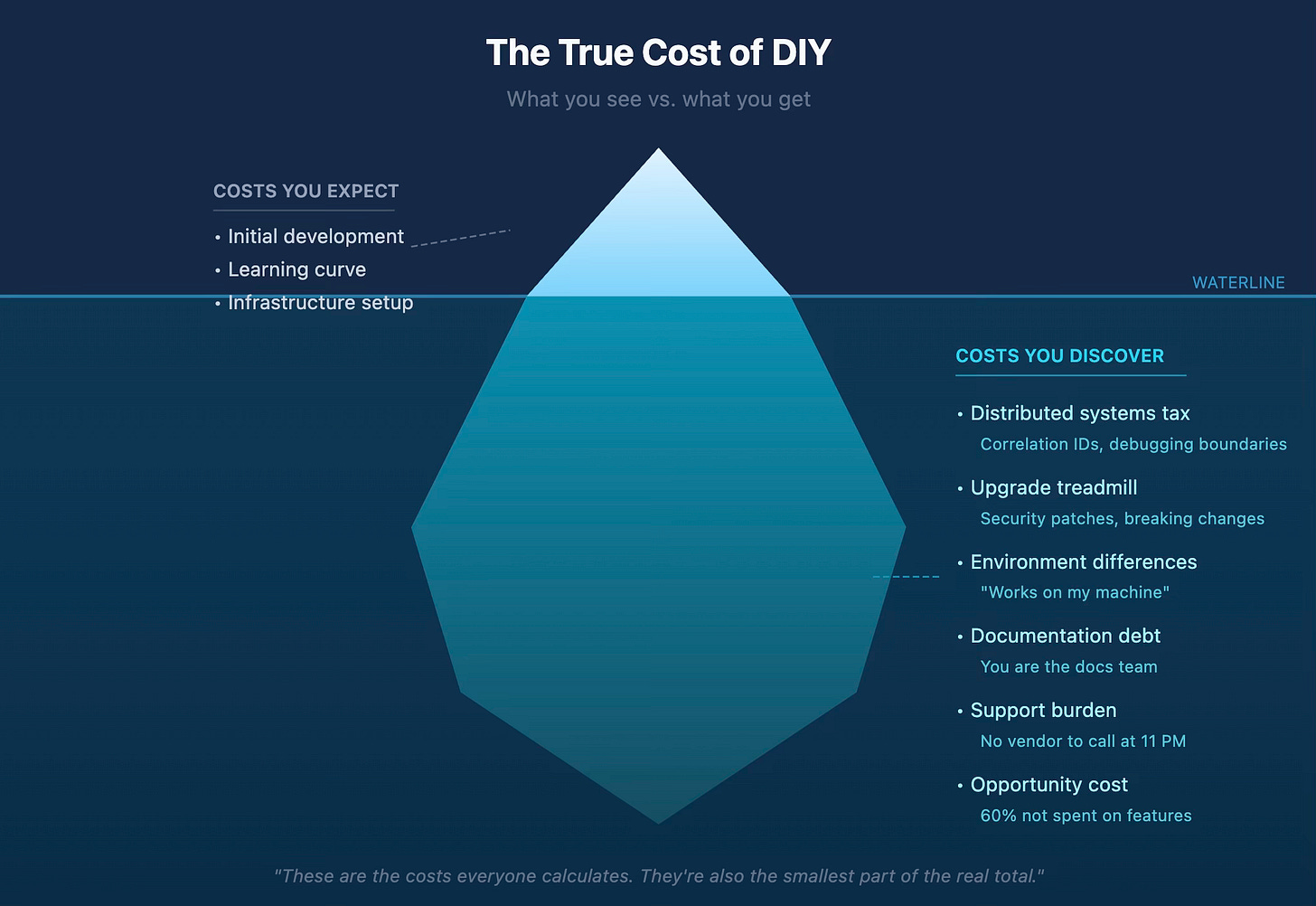

Let’s get the obvious ones out of the way. Anyone considering DIY knows about these:

Initial development time. Nights, weekends, the caffeine-fueled push to get something working. I knew this going in.

Learning curve. NestJS, Prisma, Keycloak, Traefik, Docker Compose, Terraform—each one has a learning curve. I budgeted for this.

Infrastructure setup. PostgreSQL, Redis, object storage, authentication. Table stakes for any platform.

These are the costs everyone calculates. They’re also the smallest part of the real total.

The Costs I Didn’t Expect

The Distributed Systems Tax

That LinkedIn comment nailed it: correlation IDs, traceability, network hops.

GigaChad GRC has seven microservices. Each one is a debugging boundary. When a request fails, which service caused it? The logs don’t correlate themselves.

I didn’t add correlation IDs from day one. That decision cost me a two-hour debugging session that should have been ten minutes. The request touched Controls, then Frameworks, then back to Controls. The failure happened in the second hop. Without correlation IDs propagating through headers, I was grep-ing timestamps across three log streams trying to reconstruct the sequence.

The lesson: Every microservice boundary is a debugging boundary. The architecture diagrams don’t show the operational complexity hiding in each arrow.

Features that look simple on paper touch multiple services:

“Add evidence to a control” → Controls service + storage abstraction + audit logging

“Test a control against a framework” → Controls + Frameworks + Evidence

“Generate an audit report” → Audit service + Controls + Frameworks + Evidence + Reports

That “simple” feature isn’t one change—it’s coordinated changes across services, with testing, deployment, and the prayer that nothing breaks in production.

The Upgrade Treadmill

Dependencies don’t maintain themselves.

When Keycloak releases a security patch, that’s my weekend. When PostgreSQL announces a major version with breaking changes, that’s my migration to plan. When npm audit shows 47 vulnerabilities of varying severity, that’s my judgment call on which ones matter.

Commercial vendors absorb this. They have teams dedicated to keeping infrastructure current. They test upgrades before you see them. They eat the cost of compatibility work.

DIY means you ARE the vendor. Every upstream change is your responsibility.

In the past year, I’ve dealt with:

Prisma ORM updates that changed query behavior

Breaking changes in the MCP SDK that required refactoring all three servers

Node.js version updates that broke Docker builds

Keycloak realm export format changes that invalidated my configuration

None of these were on my roadmap. All of them consumed time I’d planned for features.

The “It Works on My Machine” Problem

Development happens on my M1 Mac. Production runs on Linux. Docker papers over most differences—until it doesn’t.

Memory limits that seemed fine locally caused OOM kills in production. Network policies that don’t exist in docker-compose become walls in Kubernetes. File system permissions that work on macOS fail silently on Linux.

The first real production deployment surfaced a dozen assumptions I didn’t know I’d made.

Commercial platforms have dedicated infrastructure teams. They’ve already hit these issues. They’ve documented the solutions. You get the benefit of their experience without paying for their mistakes.

Documentation Debt

Nobody wants to write docs. I certainly didn’t.

But without docs:

Every new team member’s onboarding is a conversation (my time)

“How do I add a new integration?” gets asked repeatedly (my time)

API changes without changelogs become support burden (my time)

Six months later, I don’t remember why I made that decision (my time, debugging my own code)

Vendor platforms have technical writers. They have documentation teams. They have customer success people who update the help center.

You are the documentation team. You are the technical writer. You are customer success. Every role you don’t fill is a gap the platform’s users will feel.

The Support Burden

Commercial vendors have support tiers, SLAs, escalation paths. When something breaks, you open a ticket.

DIY means:

No vendor to call

No SLA for a fix

No one to blame but yourself

Your weekend is the incident response team

When the platform breaks at 11 PM, you’re not waiting for a vendor response. You’re debugging. When it breaks during a demo, you’re not pointing at someone else’s bug. You’re apologizing and fixing.

The psychological weight of sole ownership is harder to quantify but real. Commercial platforms let you externalize blame. DIY makes every failure personal.

Opportunity Cost

This is the hardest to measure and the most important.

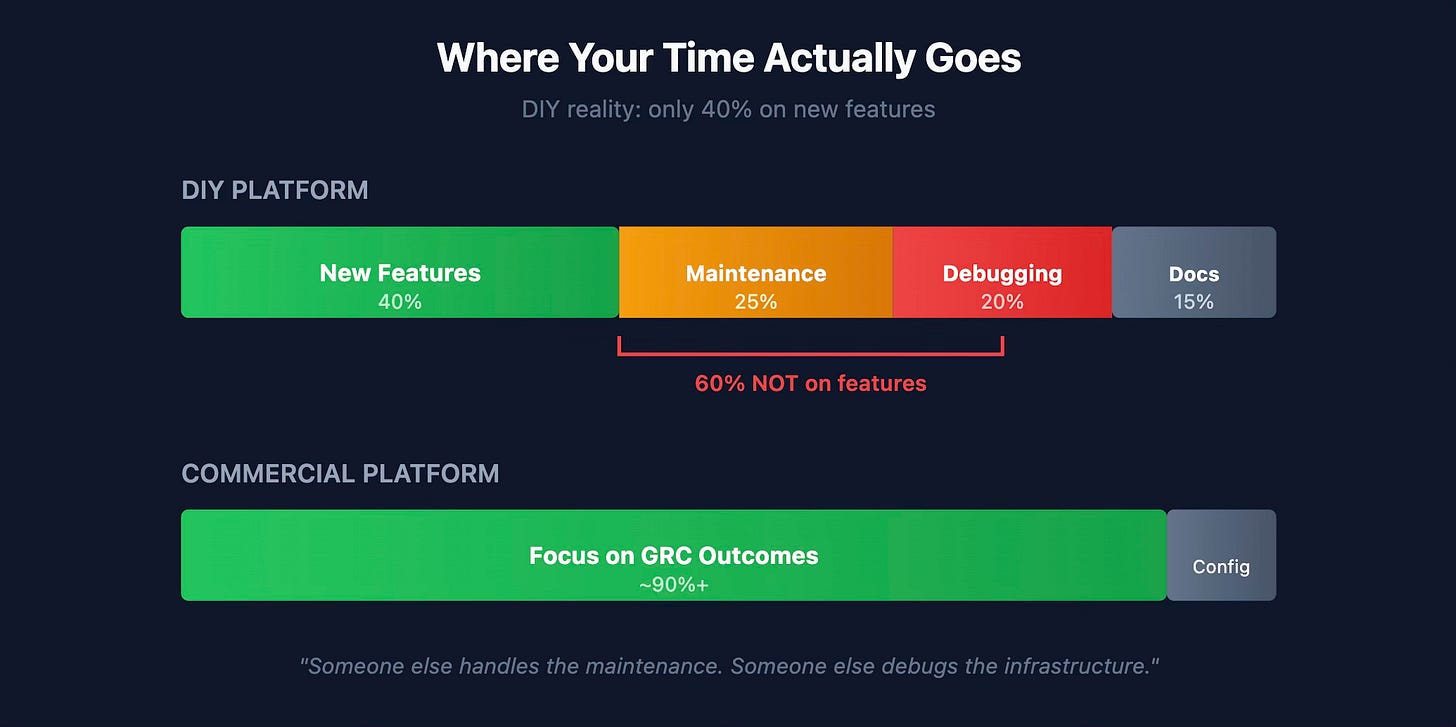

Every hour maintaining infrastructure is an hour not improving GRC outcomes. Every debugging session is time not spent on actual compliance work. Every dependency upgrade is a feature not built.

I track my time loosely. Rough estimates:

40% new features

25% maintenance and upgrades

20% debugging and fixing

15% documentation and support

That 60% not spent on features? On a commercial platform, it would be close to 0%. Someone else handles the maintenance. Someone else debugs the infrastructure. Someone else updates the docs.

The question isn’t whether DIY costs more time. It does. The question is whether you’re getting value from that time that you couldn’t get from a vendor.

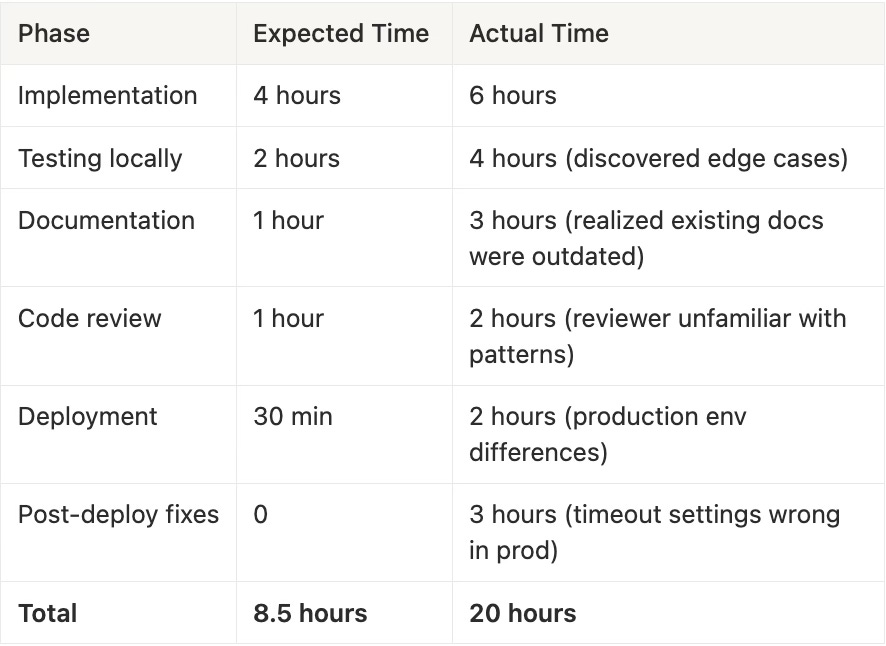

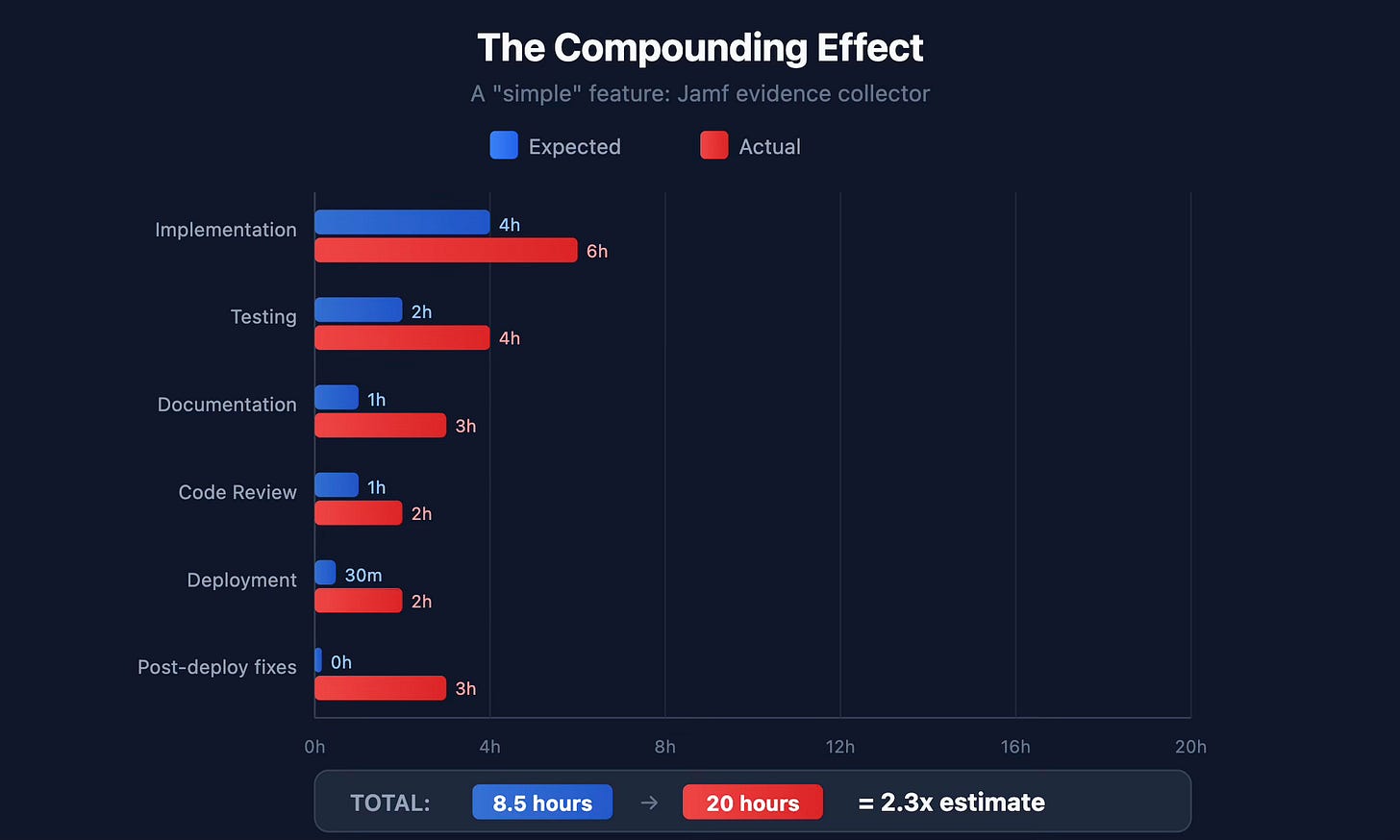

The Compounding Effect

These costs don’t add—they multiply.

Scenario: A security patch requires upgrading a core dependency. The upgrade changes behavior in ways that affect two services. Debugging the issue takes longer because you didn’t add correlation IDs. The fix requires updating documentation you never wrote. You deploy on a Friday and discover a production-specific issue. Your weekend becomes incident response.

Each cost alone is manageable. Together, they cascade.

Here’s a real timeline from a “simple” feature request:

Request: Add a new integration (Jamf evidence collector)

That’s 2.3x the expected time. And this was a straightforward feature—no coordination across services, no breaking changes, no security implications.

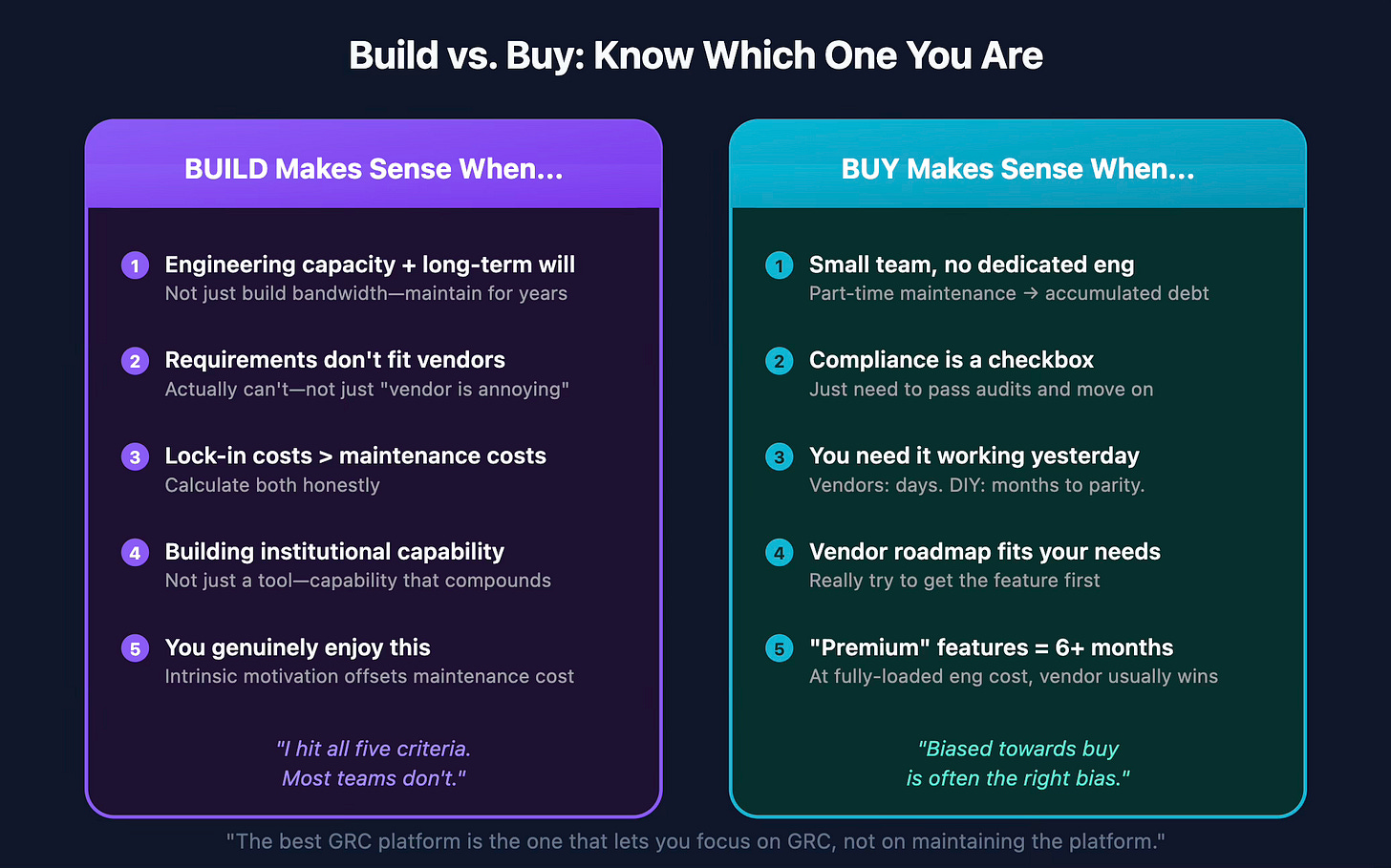

When DIY Makes Sense Anyway

Despite all this, building GigaChad GRC was right for me. DIY makes sense when:

You have engineering capacity AND long-term willingness. Not just bandwidth to build—bandwidth to maintain for years. The engineer who builds it should want to own it indefinitely.

Your requirements genuinely don’t fit commercial offerings. Not “the vendor is annoying”—actually can’t do what you need. API gating, integration limitations, workflow inflexibility that can’t be worked around.

Vendor lock-in costs exceed maintenance costs. Calculate both honestly. Migration costs are real. So is the 60% maintenance tax on DIY.

You’re building institutional capability, not just a tool. If you’re creating engineering muscle around GRC—capability that compounds—DIY might be an investment. If you just need the compliance checkbox, it’s pure cost.

You enjoy this. Seriously. If maintaining infrastructure feels like a burden, buy. If you find satisfaction in owning the stack, the maintenance cost is partially offset by intrinsic motivation.

I hit all five criteria. Most teams don’t.

When You Should Just Buy

Let me be direct:

Small team without dedicated engineering. If no one wants to own this as their primary responsibility, buy. Part-time maintenance leads to accumulated debt.

Compliance is a checkbox, not a strategic capability. If you just need to pass audits and move on, vendor platforms are optimized for exactly this.

You need it working yesterday. Commercial platforms are deployed in days. DIY takes months to reach parity.

Your vendor’s roadmap actually addresses your needs. Talk to them. Really try to get the feature. Many practitioners skip this step and build instead of asking.

The “premium” features would take you 6+ months to build. Calculate honestly: that API access costing $30K/year would take how many engineering hours to replicate? At fully-loaded engineer cost, the math often favors buying.

The Math

Rough calculation:

Vendor cost: $100K/year

DIY build cost: 2 FTE-years (at $150K fully-loaded = $300K)

DIY maintenance: 0.5 FTE/year ongoing ($75K/year)

Break-even: 4+ years, assuming no scope expansion and consistent maintenance allocation.

If you don’t have specific needs that vendors can’t meet, the vendor usually wins.

Questions to Ask Before You Build

Before you start:

Do you have at least one engineer who WANTS to own this long-term? Not assigned to it—actively wants it.

Have you actually tried to get your vendor to solve the problem? Escalated to product? Talked to their engineers? Explored workarounds?

Can you articulate specifically what you need that vendors don’t offer? Vague frustration isn’t a spec. Concrete requirements are.

Do you have production infrastructure experience, or will you learn on the job? Learning is fine—but budget the cost.

What happens when that engineer leaves? If the answer is “we’re stuck,” that’s a single point of failure.

Are you building a tool or building a product? Internal tool = lower bar. Product for others = dramatically higher bar.

If you can’t answer these confidently, the “biased towards buy” approach is probably correct.

Closing

That LinkedIn commenter was right to push back. “Biased towards buy” is often the right bias.

The GigaChad GRC posts aren’t meant to convince everyone to build. They’re meant to show it’s possible for those who have the right reasons, the right capacity, and the right expectations.

The vendor monopoly is optional. But so is the DIY path.

The best GRC platform is the one that lets you focus on GRC, not on maintaining the platform. Sometimes that’s a commercial solution with good-enough flexibility. Sometimes that’s a custom build you own completely.

Know which one you are before you start.

The author built his own GRC platform and doesn’t regret it—but wouldn’t recommend it to everyone. Still drinks too much coffee.